PHILO T. FARNSWORTH (1906-1971)

Philo Taylor Farnsworth was a 14-year-old farm boy when he came up with the concept of electronic television in 1921. During his lifetime he amassed over 160 patents for his inventions. In addition to TV, he worked on the development of radar, the electron microscope, night vision, the human infant incubator, the gastroscope, and his final frontier, a combination of nuclear energy and electronics he called “nucleonics." For a comprehensive overview of Farnsworth's life, as told by his great-granddaughter, Jessica, watch the video below.

THE BOY GENIUS

Born in a log cabin in Utah in 1906, Philo Taylor Farnsworth grew up in the Old West. His father drove a stagecoach and their farm had no electricity. He had no telephone, no computer, not even lights at night. After seeing a locomotive at the age of six, he decided he wanted to become an inventor. A summer job near Rigby, Idaho provided the fertile soil for his “big idea.”

The barn contained a stash of science fiction magazines that promised a future with flying cars, picture phones, and mechanical television. By learning to repair the farm’s broken Delco generator, he began his lifelong fascination with electrons.

THE PLOW THAT CHANGED THE WORLD

This is an actual harrow disk from the plow 14-year-old Philo Farnsworth used in 1921 to create the lines in the dirt that inspired his concept for electronic television. His “big idea” was that if he could train electrons to scan a picture from side-to-side, the way his horses moved across the field, he could send images to distant locations where they could be reconstructed line-by-line. He had not yet been to high school.

The writing on the right side of the harrow disk was put there in 2015 by Dr. Farnsworth's son, Kent, authenticating its origin. The inscription reads, "More than likely is a disk from the harrow PTF used in Utah. The source is trustworthy - Kent Farnsworth"

THE BIG IDEA

In the video below, Dr. Farnsworth's son, Kent, explains exactly how his father conceived the idea for electronic television.

THE TEACHER

When he was 15, Philo entered high school and begged his science teacher, Justin Tolman, to let him take senior-level physics and chemistry. The teacher was reluctant at first, but agreed.

One day he noticed Farnsworth drawing on the blackboard. It turned out this was the first design for an all-electronic television camera. Tolman volunteered to tutor the young genius and kept a notebook sketch of the first camera. Decades later, when RCA claimed it was impossible for a self-taught 21-year-old to invent something as complicated as TV, his former teacher showed up with the drawing. Not only could a 21-year-old invent television… a 15-year-old had done it.

ELMA "PEM" FARNSWORTH (1908-2006)

In 1926, Philo proposed to his 18-year-old sweetheart, Elma “Pem” Gardner. He wanted her by his side in the lab, telling her, “Together we’ll be working right on the leading edge of discovery.” He trained her to do technical drawing, spot welding, and she typed his lab notes chronicling the progress of each day’s experiments. Their lab journal would eventually be the crucial evidence proving Farnsworth’s “priority of invention” of all-electronic television. When he wanted to test his new invention, Pem became the first human ever televised.

THE PARTNERS

THE MOTHER OF TELEVISION

In the video below, meet Pem Farnsworth and hear her story in her own words.

THE JOURNEY BEGINS

In 1926, the 19-year-old fledgling inventor promoted an investment of $6,000 from businessmen Les Gorrell (left) and George Everson (right). Phil Farnsworth (he had dropped the “o” from his name) now began work in earnest on electronic television.

The electricity in Salt Lake City was unreliable, so Farnsworth and his new bride moved to Hollywood, California to create their first lab.

THE FIRST TV CAMERA

This is the first television camera tube Farnsworth ever built (see below). It took a glass blower over two months to create. It never worked, but it was the start. Unfortunately, a power surge during an early test caused a lab explosion and everything was destroyed. This tube, labeled number one, is the only remaining relic of that era.

1926 RECEIVER AND NOTEBOOKS

The ideas for electronic television hatched from Farnsworth’s mind almost completely developed before he built them. These concept drawings of “The Transmitting End” and “The Receiving End” from his May 1926 notebook are almost identical to his first TV cameras and the receiver tube shown below.

THE FIRST WORKING CAMERA TUBE (1927)

After the smoke cleared on his laboratory fire, Phil moved to San Francisco where, with a $25,000 investment from Crocker Bank, he, his wife, her brother, and two assistants transformed an empty loft at 202 Green Street into an electronics laboratory.

Against all odds, within one year, they produced the first working electronic television camera tube dated September 7, 1927. It was built by Pem’s brother, Cliff Gardner, based on Phil’s patents. The rounded lens resembled an eyeball and it only broadcast a single line. As his wife danced around the lab, the 21-year-old inventor said, “I said I’d invent television and there it is.” Notice how similar it is to the 15-year-old boy’s chalkboard drawing. When his backers asked when they might see some money in “the damn thing,” his next broadcast was a dollar sign.

THE DAY TV WAS BORN (September 7, 1927)

The video below chronicles how 21-year-old Philo Farnsworth and four assistants accomplished what the biggest corporations and smartest engineers in the world could not. Using rare audio recordings from a lecture Farnsworth gave at Indiana's Manchester University in 1960, relive the day all-electronic TV was born on September 7, 1927.

FARNSWORTH TELEVISION JOURNAL

The inventor’s progress is traced in this official Farnsworth Television Journal. On September 7, 1927, he wrote, “The received line picture was evident this time.” This bound volume, filled with descriptions, diagrams, and photographs, is marked as evidence in the Farnsworth patent victory over RCA.

Philo's handwritten notes (above) were typed by Pem (below) for inclusion in the lab journals.

THE WORLD TAKES NOTICE

Word of Farnsworth's success spread quickly. Soon his lab was visited by investors, dignitaries, and even silent film superstars Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks who decided television was no threat to the film industry.

FARNSWORTH IMAGE DISSECTOR & ELECTRON AMPLIFIER

This is the demonstration image dissector camera tube that Farnsworth took with him to show investors how the system worked. He had the lens sawed off to reveal a simulated picture on the optical image plate. He would explain how that image was scanned and converted into a trail of electrons to be transmitted and then decoded by a receiver.

Before he could broadcast complex images, Phil realized he would have to invent the tools to invent the tools. The first big breakthrough was the multipactor, an electron amplifier that used a single power source to energize many instruments at once. Now he could proceed.

FARNSWORTH RECEIVER & CAMERA

The first television sets needed constant adjustment and the tiny cathode ray tubes glowed blurry, greenish-gray images. This 1930s Farnsworth television and camera, recreated by Richard Grosser, reveals how much “do-it-yourself” was required.

Early television receivers were complex instruments that required precise calibration by the user. The meter on the left measured the signal in milliamperes to allow accurate tuning. Other controls centered the picture vertically and horizontally and kept the image from rolling or skewing.

Often, experimental television stations had only a few dozen viewers who could receive a signal, so consumers were given custom station call letters to affix to their tuners.

THE FRANKLIN INSTITUTE

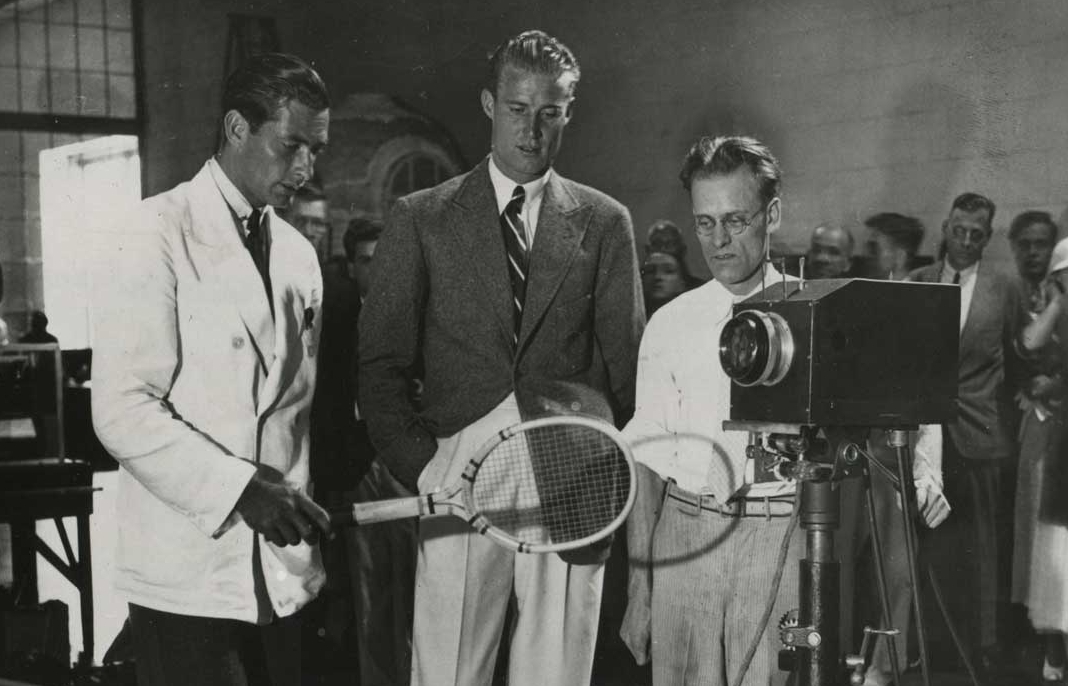

In 1934 Farnsworth successfully demonstration television at Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute. Audiences were transfixed and refused to leave. Finally he told his cameraman, “Point the camera at the moon.” The next day, 200 newspapers across the country reported the story, “The Man-In-the-Moon has posed for his first radio snapshot.”

In this rare photograph from 1934, Farnsworth (on the right behind the camera) shows the strain of keeping the demonstration television system operational while programing enough material to televise for the entire 10-day run of the exhibition.

EARLY TV STAR MICKEY MOUSE

The bright lights needed for television pictures were so intense that Farnsworth created a system for broadcasting films. A Mickey Mouse cartoon was the first. On the box, the inscription to his son reads, “Dear Skee, Hope you like it. It is one of the first films used over television (Daddy’s Television). Love from Mom & Dad – 1945”

THE RIVAL & THE CORPORATE GIANT

VLADIMIR ZWORYKIN

Russian scientist and inventor Vladimir Zworykin moved to the U.S. in 1919 to work on television at Westinghouse. On December 29, 1923, he filed a patent called "Television Systems," but the system didn’t work very well and the project was dropped. In 1929, Zworykin invented an all-electronic camera tube called the Iconoscope. It caught the attention of RCA Chairman David Sarnoff who recruited him to develop television for RCA.

DAVID SARNOFF

David Sarnoff became the first media mogul in 1917 when he formed the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) to control all the patents involved in radio. He also had visions of developing television. Sarnoff introduced television to the public at the 1939 World’s Fair and popularized it with his broadcast network, NBC.

CORPORATE ESPIONAGE AND THE PATENT WAR

By 1930, RCA still didn’t have a working television system, so their top scientist, Vladimir Zworykin, made a surprise visit to Farnsworth’s lab in San Francisco. Zworykin claimed he was from Westinghouse and they might want to license the Farnsworth system, so Philo showed Zworykin all his secrets. That night Zworykin sent RCA a telegram stealing the ideas. Once RCA had a working tube, they challenged the Farnsworth patents in court. They claimed Zworykin’s 1923 application came first, but they had no tubes, notes, or any proof that Zworykin’s system had ever worked.

As you can see, RCA’s design for the iconoscope was very different from the Farnsworth image dissector, but RCA couldn’t convince the judge theirs was not fundamentally based on his.

Zworykin/RCA ICONOSCOPE

Farnsworth IMAGE DISSECTOR

This 1935 legal victory meant Farnsworth should receive a royalty on every television made, but delays in setting a broadcast standard forced him to license his system to Germany first to televise the 1936 Olympics. Finally, in 1939, RCA paid Farnsworth a small royalty, but then announced they had invented television. Before Farnsworth could fight back, World War II halted TV production and pushed Farnsworth’s patents past expiration.

WORLD WAR II STOPPED TELEVISION… BUT NOT FARNSWORTH

In 1942, the United States government converted all television production into wartime electronics. Farnsworth’s contributions included radar, the first drone videography, infrared lenses and night-vision sniper-scopes for rifles, and even a quick-drying system for wood products.

THE IATRON TUBE

Farnsworth concentrated on research in his post-war government contracts, creating satellite cameras, 3-D industrial television and the iatron “memory tube” which is the basis of today’s computer flat screens.

FARNSWORTH TV SETS

By the time TVs finally went on sale, Farnsworth’s patents had expired and anyone could use his technology without paying a royalty. Farnsworth’s company did manufacture some televisions before going bankrupt. Despite brief partnerships with Philco, Capehart, and ITT, RCA’s marketing power all but buried him.

The television in this exhibit was Farnsworth's personal set and one of the last sets manufactured at his factory in Indiana.

In the clip below, Dr. Farnsworth's son, Kent, describes the details of a rare Farnsworth signature television.

When he realized he would not be taking part in bringing his invention to the public, he had a breakdown. He left his lab and went to Maine to go fishing. Then he came up with an idea that he thought was even better than television.

I'VE GOT A SECRET

The clip below is Philo Farnsworth on the game show "I've Got A Secret" in 1957. It's the only time Philo was seen on commercial television and no one knew who he was. Especially interesting are his predictions about the future of television and nuclear fusion.

Below is the letter Philo received, along with a check, as his prize for stumping the panel and winning "I've Got A Secret." He was also awarded a carton of Winston cigarettes.

THE FUTURE

Philo Farnsworth’s last experiments aimed to create clean, safe, unlimited energy using the principles of the H-bomb. He felt his “Fusor” (pictured) could power cars, homes, and even spaceships. Its applications included altering weather patterns to increase food production, killing viruses that cause cancer, and powering human settlements on Mars. His small-scale tests were successful, but poor health and insufficient funds doomed his development of “nucleonics.”

FIRST MAN ON THE MOON

On July 20,1969, as Neil Armstrong took his historic first step on the Moon, Philo Farnsworth told his family, “OK, turn the damned set on”. He watched as the world marveled at the live television pictures from the moon. But Philo wasn't just an observer. Month earlier, when NASA was selecting the perfect television camera system to use on the Moon, they chose Philo's original image dissector. It had no moving parts and the electromagnets created their own gravity. His satellite cameras had already withstood the rigors of space travel. So Philo Farnsworth’s story had came full circle. His camera being the first to televise the Moon in 1935, and the first to televise from the Moon over three decades later. When his wife, Pem, asked him how it made him feel, he said, “This makes it all worthwhile. Before, I wasn't too sure."

RECOGNITION

Throughout his lifetime, fame and fortune eluded Philo Farnsworth. After his death in 1971, his wife, Pem, devoted her life to setting the record straight starting with her autobiography “Distant Vision.” She worked tirelessly to have a postage stamp and a posthumous Emmy award in his honor. In 1990, the schoolchildren of Utah raised funds to have a statue of Philo erected in the Utah State House and U.S. Capitol.

Pem Farnsworth's autobiography, "Distant Vision: Romance and Discovery On An Invisible Frontier," is a revealing portrayal of Pem's life with the man who invented television.

Since 2003, the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS) has awarded the Philo T. Farnsworth Corporate Achievement Award to companies who have significantly affected the state of television and broadcast engineering.

"The Farnsworth Invention" is a stage play by Aaron Sorkin adapted from an unproduced screenplay about Farnsworth and Sarnoff

In 1983, Farnsworth was honored in a set of four U.S. postage stamps along with groundbreaking scientists Charles Steinmetz, who pioneered alternating current, Edwin Armstrong, who invented FM radio, and Nikola Tesla, who, like Steinmetz, did theoretical work with AC power and invented the induction motor.

A bronze statue of Farnsworth sits inside the Utah State Capitol, in Salt Lake City.

A bronze statue of Farnsworth represents Utah in the National Statuary Hall Collection, located in the U.S. Capitol building.

In March 2008, George Lucas had a statue of Farnsworth installed in front of the Letterman Digital Arts Center in San Francisco at the Presidio.

THE CURATOR

Curator, Phil Savenick, poses with Pem Farnsworth at the 2003 Emmy Awards. They're joined by the ghost of her late husband, Philo.

This painting depicting the evolution of Farnsworth's invention was created by exhibit curator Phil Savenick.

Phil Savenick is a television producer and a televisionary artist. As a writer-producer, Phil Savenick has created many of television's most highly-regarded compilation documentaries about TV and broadcast history. He produced CBS's “50 Years of Television: A Golden Celebration,” “ABC's 40th Anniversary Show,” “HBO's 20th Anniversary,” “The Mary Tyler Moore Show's 20th Anniversary,” and “Rick Nelson: A Brother Remembers”. He co-produced “The Museum of Television and Radio Presents The Funny Women of Television,” “M*A*S*H: Our Finest Hour,” “Phil Donahue’s 25th Anniversary Special,” “The Best of Disney’s 50 Years of Magic,” and HBO’s “Monty Python Reunion Tribute” in 1998. His film clip tributes have appeared on the Emmys, Oscars, Grammys, SAG Awards, Comic Relief, and specials for Bob Hope, Jacques Cousteau and dozens of others.

His montage sequences were featured in the movie biographies “This is Elvis,” “Imagine: John Lennon,” and the TV specials “Heroes of Rock n Roll” and “Motown 30: What’s Going On” as well as the Grammy lifetime achievement tribute film for Paul McCartney. Phil received gold records for his videos with Elton John, Billy Joel, and Tom Petty.

He has thrice been Emmy-nominated, as co-producer of “Donald Duck's 50th Birthday” and “Great Moments in Disney Animation,” and again for his editing on the 75th Annual Academy Awards. In 1996, Phil produced the Emmy winning “20 Years of Comedy On HBO,” which won him the CableAce for best comedy special. His special “100 Years of the Hollywood Western” garnered the Cine “Golden Eagle” award, a Film Advisory Board award, and the western writers “Spur” award for best documentary.

Phil and his production company, TV IS OK Productions, created and produced the Disney Sing-Along Songs, the most successful made-for-home-video “kid-vid” series of the 20th Century. In addition to the TV specials, music videos and electronic press kits, he also produced the supplementary programming for deluxe DVD editions of “The Sixth Sense,” “Monsters Inc.,” “Some Like it Hot,” and won the prestigious Best DVD of the Year for both “Toy Story’s Ultimate Toy Box” in 2000, and “King Kong Special Edition” in 2006. Most recently, Phil produced the “Painting With Ghosts” series of art adventures and “Beverly Hills: 100 Years, 100 Stories” for the City’s centennial.